78 years of Indian independence and Hindi Imposition Controversy still lingers.

India’s 1950 Constitution named Hindi (in Devanagari script) as the official language of the Union, with English assured as an associate language. Importantly, no language was made the “national” language.

Today Hindi is the single largest mother tongue (about 43.6% of Indians) and serves as a lingua franca in much of north-central India. Yet this dominance has repeatedly sparked backlash. Critics in many states call Hindi’s promotion at the national level a form of linguistic imposition.

They point out that the Constitution’s framers deliberately avoided declaring any language supreme, and that India’s federal structure recognizes 22 scheduled languages. This report investigates how Hindi’s push for “supremacy” – in education, administration and media – has triggered protests and legal debates across diverse regions, drawing on official data, historical facts and voices of affected communities.

Historically, the choice of an official language was fiercely contested. In the Constituent Assembly (1946–49), delegates from Hindi-speaking North India insisted the Constitution be drafted in Hindi, while speakers from Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Bengal and elsewhere demanded English for precision in legal matters.

The compromise declared Hindi (Devanagari) as the official Union language, but allowed continued use of English “for all official purposes” past the originally planned 15-year transition. The Assembly explicitly refused to name any “national language”.

In practice, Hindi’s official status was strengthened by Article 343 and later the Official Languages Act of 1963, which let Hindi become the primary official language while English “may” continue.

But even this arrangement caused confusion: some Hindi advocates took “may” to mean “should”, prompting fears that English would end in 1965 unless each non-Hindi state agreed otherwise. The resulting ambiguity triggered fears of abrupt change.

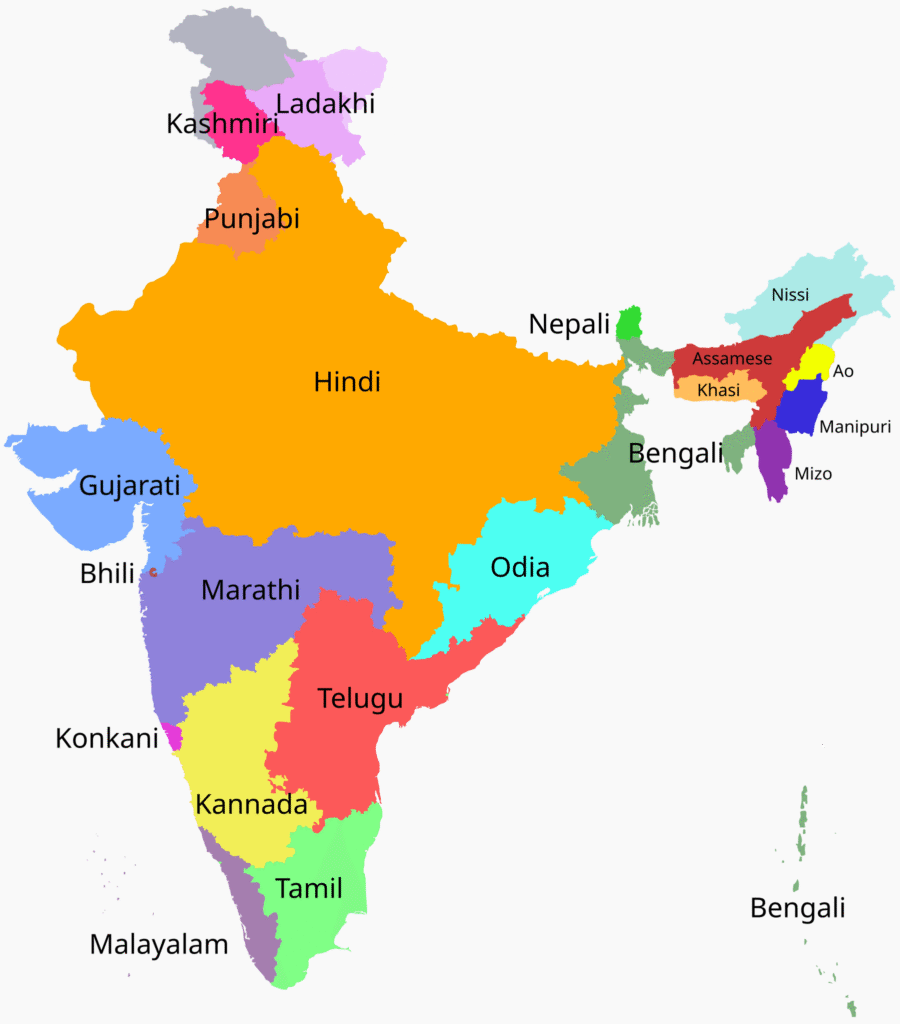

India’s map of official languages (above) underscores the federal linguistic mosaic. Hindi is official in most north and central states, while South Indian states (Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala) and eastern states have non-Hindi official languages. For example, Tamil Nadu’s sole official language is Tamil, Kerala’s is Malayalam, and Karnataka’s is Kannada.

This regional diversity has long fueled resistance: as 1965 approached, leaders from Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, West Bengal, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh all raised alarms. These states insisted that English remain an associate language. Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s plan to make Hindi the only official language by January 26, 1965 provoked massive agitation – particularly in Madras State (Tamil Nadu).

Students and activists organized strikes and parades; some protestors set themselves on fire. With dozens of lives lost and thousands jailed, Tamil leaders forced Shastri to retreat. In 1967, the Official Languages Act was amended so Hindi’s ascendancy would only take effect after all states that had not adopted Hindi gave unanimous consent.

Regional Reactions and Agitations Against Hindi Imposition Controversy

Resistance to Hindi has remained strong in many non-Hindi regions. Tamil Nadu stands out for sustained protests. The first major anti-Hindi movement was in 1938 under the Self-Respect Movement (Periyar E.V. Ramasamy) and the Justice Party, against imposing Hindi in Madras Presidency schools. Decades later, when Shastri moved to abolish English in 1965, the Tamil populace erupted in what became a historic agitation.

Communist and Dravidian parties capitalized on Tamil pride, and the DMK (founded 1949) led street protests. A recent India Today report recalls that 1965 wave of self-immolations and poisonings “raged on” until Shastri promised to keep English alongside Hindi. Today Tamil Nadu’s current leadership continues to oppose Hindi imposition. DMK leader Udhayanidhi Stalin warned in 2025 that if the Centre presses the issue, “thousands of youths are ready to sacrifice their lives” for Tamil identity.

Kerala, with its own strong linguistic identity, has likewise insisted on three-language education but opposes any forced Hindi. Kerala’s Higher Education Minister R. Bindu (CPI-M) told reporters that the state “has always encouraged a three-language policy” but is firmly “against the imposition of Hindi”.

Bindu emphasized that Malayalam would remain prominent and that Kerala even encourages foreign languages. The government has set up language institutes and repeatedly stated that mandating Hindi would undermine Kerala’s pluralistic ethos. Like Tamil Nadu, Kerala has defied aspects of the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020 (which advocated Hindi as one of three languages) and has clashed with the Centre over delayed funding tied to language reforms.

Karnataka joined this pushback in 2025. The Congress-led state government floated a two-language policy (Kannada + English) in response to national calls for three languages. State leaders openly said forcing Hindi as the third language would create “discord” and hurt students from smaller language groups like Tulu or Kodava.

Former Supreme Court judge Niranjanaradhya (on a language-policy panel) warned that early multilingual curricula add burdens and lower cognitive achievement, arguing that keeping to Kannada and English would be “better”. These proposals have alarmed educational groups: the Karnataka Hindi Education Board pointed out that over 17,900 students scored a perfect 100 in the state secondary Hindi exam (more than any other subject), and threatened legal action if Hindi were dropped (fearing job losses for 15,000 teachers).

The debate illustrates a familiar dilemma: regional leaders demand respect for the mother tongue, while some educators note that many students already perform well in Hindi.

In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (the Telugu-speaking states), however, the response has been muted. As journalist Jinka Nagaraju notes, there has been “never an anti-Hindi murmur” in these states except for one 1965 episode. Telugu politicians and media have generally adopted the three-language formula (Telugu, Hindi, English) without protest. This contrasts sharply with Tamil Nadu’s oppositional stance.

Experts explain that long periods of Urdu and Persian rule in Hyderabad fostered a multilingual culture, and after the states’ creation, Telugu nationalism took a back seat to other politics. The one notable upheaval occurred in January 1965, when Andhra students violently opposed making Hindi the sole official language. Even that was resolved by government concessions (job guarantees for Hindi teachers). Since then, Telugu leaders have largely treated language policy as a non-issue.

The North-East has seen its own conflict. In April 2022, Union Home Minister Amit Shah announced Hindi would be made compulsory up to Class 10 in all eight northeastern states. Literary and student bodies from Assam, Manipur and beyond immediately denounced this as “Hindi imposition”. The Assam Sahitya Sabha argued that resources should instead nurture Assamese and indigenous tongues, warning that forcing Hindi spells a “bleak future” for local languages.

A coalition of student unions insisted on a true three-language policy: they said each child’s mother tongue should be mandatory in school, with Hindi at most an optional third language. Regional parties echoed these concerns. For example, Assam’s Raijor Dal recalled Clause 6 of the 1985 Assam Accord (which guarantees protection of Assamese language) to reject any sidelining of Assamese.

In Manipur, groups like MEELAL (which preserves Manipuri manuscripts) saw the Hindi mandate as an ideological push toward “one nation, one language” – a threat to their cultural heritage. While the Assam chief minister defended Shah’s statement as aspirational, civil society pressure forced New Delhi to retreat from making Hindi compulsory in the region.

Even in Eastern India such as West Bengal, social frictions emerge. Late 2024 saw media accounts of clashes between Bengali and non-Bengali residents of Kolkata. One viral incident showed a Bengali woman demanding fellow passenger speak Hindi on the metro, prompting outrage. The city’s municipal body was also embarrassed when a public signboard was discovered written only in Hindi and Urdu – it had to be replaced with Bengali included after local protests.

West Bengal’s leaders reacted firmly: Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee sought classical status for Bengali to affirm its heritage, and party leaders openly defended Bengali speakers against what they saw as Hindi chauvinism.

At the same time, some Bengali politicians criticized their own community for neglecting the mother tongue, noting how even locals increasingly favor Hindi-language songs and media. These episodes highlight the complex identity stakes involved – even outside the South, language can ignite tensions between native and migrant populations.

Education and Language Policy

Central education policy has been a major battleground. Since the Kothari Commission (1964–66), India has formally endorsed a “three-language formula” for schools: typically this means a regional language (or mother tongue), Hindi, and English. But its implementation has varied. Many Hindi-speaking states teach Hindi plus English plus one other language. In non-Hindi states, the formula often leads to controversy. For example, Tamil Nadu historically chose to teach Tamil and English but resisted adding Hindi.

Recent National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 reiterates the three-language goal, which prompted renewed protests in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Delhi’s approach (as revealed when it delayed education funds to Tamil Nadu in 2024) is seen by critics as coercive. The controversy is not academic: in Karnataka, Karnataka Legislative Council Chair Basavaraj Horatti cited election data to show Hindi performance has been solid – over 17,900 students scored 100/100 in Hindi SSLC exams (more than any subject).

Horatti argued that discarding Hindi would arbitrarily penalize these students and 15,000 Hindi teachers who rely on it, while offering no real educational benefit. The key data point was: in all of Karnataka, more students pass Hindi than in most other subjects. This was contested by others who note that many of those students are already fluent in Hindi (some are children of migrants) and that the rest of India’s population needs Hindi instruction for national exams and communication.

Legal battles have even emerged. The Karnataka Associated Managements of Primary and Secondary Schools warned of lawsuits if the government tries to drop Hindi from the curriculum. Tamil Nadu has resisted implementing NEP’s three-language provisions; in 2024 it deferred them until further notice, calling them a partisan “saffron agenda”.

Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, in turn, accused the Tamil government of hypocrisy, pointing out that Tamil Nadu had previously sought Hindi programs to receive funds. These tit-for-tat charges illustrate the charged political atmosphere. On the ground, parents and educators worry about exam preparation and future opportunities – yet many students perform poorly in Hindi tests if it’s not their home language.

Media and Cultural Influence

Hindi’s dominance is also evident in India’s media landscape. In print journalism, a handful of Hindi dailies command the largest audiences. A Media Ownership Monitor study found that just four Hindi newspapers (Dainik Jagran, Hindustan, Amar Ujala, Dainik Bhaskar) capture over three-quarters of Hindi newspaper readership. Other regional press markets (Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, etc.) are also highly concentrated, but each language segment is mostly separate. Broadcast media is even more centralised. The state-run All India Radio holds a monopoly on news radio broadcasts nationwide.

Private FM channels may be common, but they cannot air news – only music and entertainment – by law. Television ratings are opaque (BARC keeps data secret), but anecdotal evidence shows that national news networks broadcast in Hindi reach huge audiences.

Bollywood and other Hindi cinema remain culturally influential: as of 2024 Hindi films still account for about 40% of India’s box-office revenue, a drop from majority share a decade earlier. (Regional films collectively now claim the majority share.) In urban areas and on the internet, many Indians consume more Hindi-language content than regional-language content, though English and local media also play strong roles in their regions.

Outside India, federations have managed multiple official languages in different ways. In Canada, English and French are both national official languages by constitution, with equal status and legal protections. Federal law mandates that all institutions provide services in both languages, and minority language rights are protected (e.g. French speakers outside Quebec, English in Quebec).

In Switzerland, four languages have official status (German, French, Italian, Romansh). In practice, most government business is in the local language of each canton: e.g. German and French each govern large communities. These systems contrast with India’s lack of a truly neutral federal language – Hindi often operates as the de facto link language, even though the Constitution envisions a multilingual approach.

Perspectives from Politics, Academia and Civil Society

The debate over Hindi is fiercely partisan. The ruling BJP, rooted in Hindutva ideology, has often promoted Hindi as a unifying national tongue. Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s 2022 announcement that Hindi was the “language of India” exemplified this view. Leading BJP figures argue that Hindi helps integrate diverse regions. Critics, however, see such statements as ideological.

The DMK, Left parties and others on the non-BJP side condemn any mandate on Hindi as a cultural imposition. Tamil Nadu’s government spokespersons routinely accuse the Centre of treating the NEP and other policies as “saffron agendas” to undermine regional languages. Andhra Pradesh’s TDP (when in power) abandoned language rhetoric entirely, focusing instead on caste and development issues (part of why Telugu pride is currently subdued).

Legal experts and educationists are divided. Some scholars argue India’s frayed linguistic policy actually violates fundamental rights, because it coerces minorities without constitutional consent. Others note that the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld English as a constitutional right of courts (Art. 348) and that any change must respect the federal balance.

For example, no court to date has explicitly outlawed Hindi instruction. Meanwhile, grassroots activists have framed the issue as one of human rights. The Asom Sahitya Sabha urged the government to “reconsider” forcing Hindi in Assam schools, invoking the Assam Accord’s Article that safeguards Assamese culture. Meitei activists in Manipur spoke of rewriting history if a larger group’s language is imposed. Even in North India’s Hindi heartland, commentators sometimes point out that no one forces southern states to adopt their language – they say, why then force Hindi elsewhere?

Conclusion

India’s linguistic tapestry is vast. The issue of Hindi’s role crystallizes the tension between national integration and regional identity. On one hand, many ordinary Indians across regions learn Hindi (and English) to communicate and find employment, and Hindi serves as a practical link across the country. On the other hand, communities argue that democratic equality demands protecting their mother tongues in education and administration.

The evidence is mixed: Hindi’s share of speakers is growing (it remains the fastest-growing language by raw numbers), but regional languages like Bengali, Marathi, Telugu and others still thrive. Other multilingual federations show that formal equality (as in Canada’s bilingualism or Switzerland’s multi-lingual cantonal system) can work, but India’s model has been more ad hoc and contested.

In this investigation, facts and testimonies paint a complex picture. From fiery 1965 protests to 2025 parliamentary debates, Hindi’s rise has never been uncontested. Political parties and civil society remain sharply divided. Academics note the educational challenges, and regional governments cite cultural rights. Any language policy in India is bound to have both defenders and detractors.

The central question remains whether Hindi’s use can be expanded by choice and utility – or will be seen as forced “supremacy.” The data and expert voices suggest that balanced solutions (e.g. optional Hindi, strong native-language education, and respect for English) may be the only way to honor India’s unity without eroding its pluralism.

Sources: Government data, major news investigations and academic sources have been used throughout. (See detailed references below.)

Wikipedia, Indian Express, India Today, Kerala Language Row, Indian Express, Media Ownership Monitor, North East Groups Row